Detroit Techno

byIt is hard to imagine the world without usual things. In 1981, modern techno, house and trance music didn’t exist. Not to mention the subgenres: jungle, garage and European hardcore. The available electronic diet included only ambient and electronic music of different kinds with a strong synthetic flavour. Techno, which emerged during the decline of Detroit in early 80s, is probably the most studied genre of electronic music. Experts explain this vivid interest by the initial meaningfulness—the movement had its own philosophy. Chicago House, which was created around the same time, a four-hour drive from Detroit, didn’t have this—house was just new music for the dancefloor, coming to replace disco which was getting boring. Techno, from the first day of its existence, was presented as the music of the future.

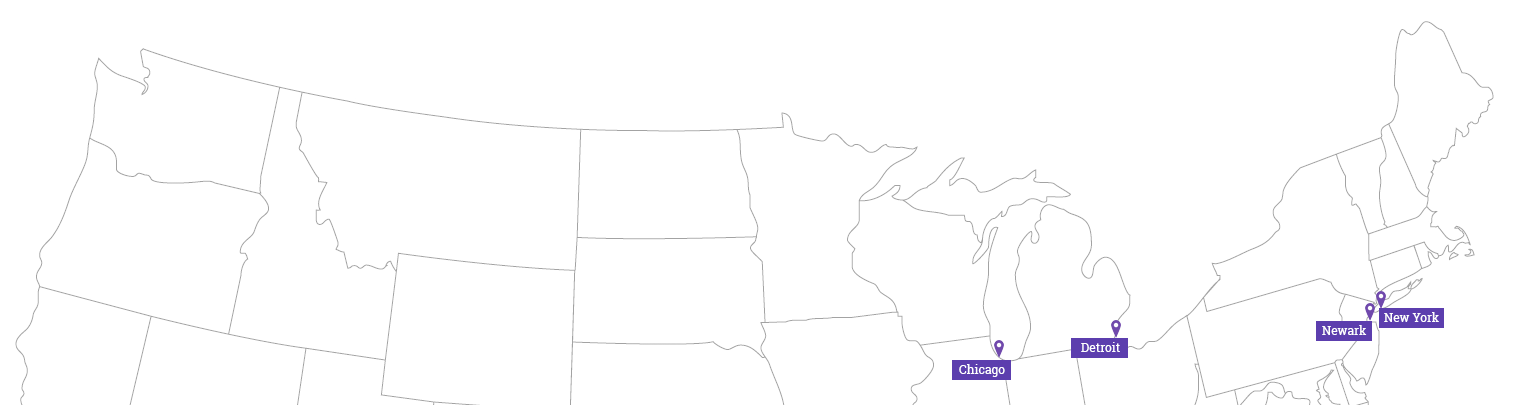

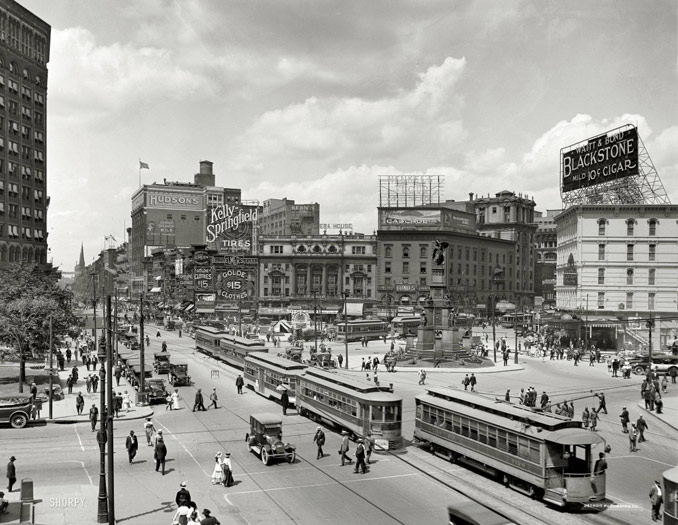

The style is closely linked to the place. The history of Detroit’s self-destruction is important for understanding the nature of the genre. Its creators claim that any other city in America couldn’t create techno. And then they show majestic and beautiful art-deco buildings that are either abandoned and fenced or turned into a parking lot to the journalists who make films about this cultural phenomenon. Now Detroit is a city on the periphery, which became a dressing room to try on new depressing epithets, but in its best years, it was the fourth biggest city in terms of population (after Philadelphia, Chicago and New York). Since Henry Ford founded the world’s first car manufacturing plant here, at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, the city became one of the centres of the US. Soon the Big Three would settle here: General Motors, Chrysler, and Ford Motor Company. Detroit quickly attracted the best hands and brains in the US—the worker’s salary here was two times bigger than in other cities of the country, so the city became home to hundreds of thousands of immigrants: Europeans as well as black and white Americans. Racial conflicts did occur, but the Northern States had a better attitude towards black people than their native South, where segregation was normal (each race had their own districts, schools, hospitals, washstands and seats in the bus). In the 30s, the Congress of Industrial Organizations started to support workers of colour, and from the 40s, the black population of Detroit was increasing by 10% every ten years.

After reaching the peak of its development in the 50s, the city began to break down under the force of its own greatness. A rich city has expensive land. So, this rich city has been fully built up. White people of Detroit started moving to cheap suburbs: further away from factories, skyscrapers, noise, criminals, and expensive rent. This was later called white flight. Another thing that contributed to the repopulation of the outskirts was the 1944 Act which granted generous governmental benefits to WW2 veterans. Along with a cheap loan to start his own business or study in university, a soldier could take out a mortgage for a suburban house with a low interest rate without initial payment. Statistics say that, during the first nine post-war years, 9 million Americans left the cities (1/15 of population at the time). The government of Detroit tried to take advantage of the situation. They started a campaign to promote personal cars. Popular public transport was mocked and became the territory of the poor and feeble. Motor City needed sacrifices. The lack of buses in the suburbs made those who had just moved buy a car. The others also enjoyed coming home in their own cars instead of being crammed into public transport. After five days of black riots, caused by the law prohibiting the selling of alcohol after 5 pm (the end of the working day), which was suppressed with tanks in 1967, the city began to decline even faster. But the last nail in the coffin of its future was the 1973 oil crisis.

Egypt and Syria didn’t forgive the big losses and possible defeat of their capitals by the Israeli forces. Arab countries didn’t acknowledge the victory of Israel in the Yom Kippur war and proclaimed an oil embargo on the allies of Israel (the United States and Western Europe) through OPEC. By reducing the extraction of raw materials, they increased the demand for it and created an artificial deficit. A barrel became four times more expensive—its price rose from three to twelve dollars. Life in the United States stopped. The postwar US, unlike Western Europe, hadn’t experienced problems with fuel: the biggest producer of the world, affordable prices, enough gasoline for everyone. In such a situation, the car makers could afford to produce heavy, expensive and gas-guzzling transport. Now, the government was begging the population to save fuel, to start their cars only in a case of extreme necessity and only with low speeds. Some gas stations were closed, other had terrible queues with limits on purchases. Drivers were abandoning their cars. Row upon row of long beautiful cars could be found: dusty Pontiacs, Fords, Chevrolets, and Cadillacs. Gasoline saving cars needed some time for production and, since there was no time, the country was saved by a huge amount of imported European and Japanese subcompact cars. The city still hasn’t recovered, even forty years later. Thousands of new models were standing without demand in the stores of Detroit’s major car-makers during the crisis.

Juan Atkins

In Detroit, there is the symbolic

Korg MS-10

At the end of school, Juan bought a small monophonic synthesizer, the

It was a sequel to Future Shock, a book about formation of post-industrial society published in 1975. By waves, the author means the stages of development of the world order. Agricultural society lasted for almost two thousand years, the Industrial Age for a century and half, and post-industrial society started after WW2. By future shock, Toffler means the state of frustration, rejection and even resistance to changes. The world is changing very fast and it applies not only to culture or scientific and technological progress but also to society (women and black people’s fight for equal rights, the establishment of a secular state and attempts of the church to gain an influence on people’s minds), to the economy (rampant inflation, unemployment, devaluation of the national currency) and politics (state dissolution). People are overwhelmed because of all the changes. Of course, they’re shocked by the present but they’re even more concerned about the future which is becoming more uncertain. Atkins was engrossed with The Third Wave. In the twelfth chapter, he found the word techno, which was used for techno rebels (the agents of the third wave who vote for technologies which are safe for the Earth as well for people, and which need to be controlled).

Giorgio Moroder

Atkins uses the term techno as a criterion for this new artificial music, in which every sound is made by the synthesizer. This includes the participants of British New Wave, the experimenters of Kraftwerk, the creators of electro-funk from the ghetto of New York, and the founder of electrostatic disco, the mustachioed Giorgio Moroder, who had then just made two revealing albums: From here to eternity and E=MC2, with the immortal Chase between them. “At the time synthesizers were relatively new for the public. The only people that played synthesizers at that time was Stevie Wonder. When these affordable synths came out, like the Mini Moog and the

Giorgio in the mix

Giorgio in the mix

Rick’s studio, with curtained windows and lamps near the equipment, looked like a spaceship to Juan: “I walked into Rick's room and was blown away. He had an ARP Odyssey, ARP Axxe, Roland RS09 string machine, the ARP analogue sequencer and an early Roland sequencer, and tbe Boss DR55 Dr Rhythm. I had my little

Cybotron — Alleys of your mind 1981

From Alleys of your mind single, Deep Space

Atkins: “The second release came out, Cosmic cars, the one that everybody played at the parties. We only had a 45 release on Alleys of your mind. The disco era produced the disco version which was the 12 inch single. DJs like Ken Collier didn’t play 45 records, he played 12 inch discs, but the 12 inch disc was kind of new, especially to the consumer. You had some promotional only 12 inches that you couldn’t even buy, that were just straight up promotional copies. When you went to the store it was on 45. That was the thing with Alleys of your mind, a lot of DJs couldn’t play it because it was on 45. It was funny because I saw one DJ actually have one pasted to a 12 inch record, in order to have the 12 inch format [laughs]. That’s how bad he wanted to play the record, you know what I mean? Nobody still had their 45 thing [adapter] for 1200 turntables, so people just didn’t play them. That was the drawback from Alleys of your mind and was one of the clashes that me and Rik would have. I would say, although it would have cost slightly a little more money, ‘man, we have got to release this record on 12 inch format,’ but he didn’t listen to me. Economically it was a sound decision because we sold a lot of those 45s. Even though it was a single, it [a 12 inch] cost you the same amount that it would cost to press a full album for just one song. Big record companies were able to do that but independents, small upstart shoestring budget labels, couldn’t be paying album prices for just one damn record.”

Charles Johnson, involved in the success of techno music, is a person whose contribution the founders of the genre remember with gratitude. He worked as a DJ on the radio station WGPR Detroit under the pseudonym Electrofying Mojo and for several years he opened the night show ‘Midnight Funk Association’. “Mojo had a tremendous impact on musical tastes in Detroit,”—all the founders of techno say unanimously. He played George Clinton’s funk bands: rock-influenced Parliament and psychedelic Funkadelic—bands that had a strong position in Detroit. He also played Prince and Frank Zappa as well as the representatives of American and British new wave:

Richard Davis

Methane sea

1978

Mojo knew Rick Davis—a fragment of Methane sea released by the veteran musician played in the opening theme of the show. After the show, at two and half, Derrick May gave the tape with Alleys of your mind to his idol, and today one third of the techno scene worships him. Mojo favours innovators. The single, released by Rick and Juan, sold fifteen thousand copies. Atkins laughs: “I had people come up to me and say they thought Cybotron was some white guys from Europe. People couldn’t believe we were actually Detroit musicians.” The duo’s music was played on the radio and now not only on their patron’s programme. People calling to request a song shouted: “Cybotron! Cybotron!”

Cybotron — Cosmic cars 1982

From Cosmic cars single, Deep Space

After the success of the second record Cosmic cars, used in the Detroit Grand Prix, California became interested in Cybortron. “We had a following",—Atkins recalls. “Alleys of your mind was huge in Detroit and then we came with Cosmic Cars. We had a new sound and we were selling tons of records. The independent distributors couldn’t ignore that because they would go into the store and we’d be number one on the chart. They’d be trying to chart their records and they’d go into the store and be, ‘well hell, who are these guys? They’re number one on the chart, we are here trying to pay you to get on the chart and we are not distributing their record?’ So eventually they had to get us under their wing. A one stop is what you call a wholesale house where retailers would go and buy all of their products. You had stores that were competing against each other for this Cybotron record and we had one store tell us not to sell it to nobody else. If we went and sold it to the other one stop then they would stop selling it. All of that crazy politics going on and they had certain DJs under their wing, certain radio stations. All of a sudden your record would be playing on one radio station and then it would stop playing on that station and start playing on another because you sold to the other distributor, it was crazy.”

Finally, the Enter album, full of social and religious connotations, came out. “There is not a brick left standing where I grew up. The neighborhood is gone, the schools are gone. My childhood no longer exists. You ever see that 1953 version of War of the Worlds with Gene Barry?”, Rick Davis asks. “When the general tells him, ‘Nothing remains.’ I grew up in those alleys, that post-industrial wasteland. That deurbanization.” The Line tells the story of the queues at the Detroit labour exchange; Industrial lies became a message to Reagan’s neo-conservatives with their huge military expenses in the framework of the "peace, through strength" policy. El Salvador is about the fight between the United States and the Soviet Union for influence on the state in Central America (a very personal topic for Davis, who was in the middle of a similar fight in Vietnam; he imitates the sounds of tracers and helicopter blades with synthesizers). Enter is about the transition into a new reality, Clear is about strengthening positions: forget everything old, don’t cling to the past, start all over again.

Cybotron — Clear 1983

From Clear single, Deep Space

Cybotron — El Salvador 1983

From Enter album, Fantasy

Gary Numan

Cars

1979

The hit Cosmic cars was a dedication to the personal cars of each of the founders of the band: Davis’ black and yellow Dodge Omni and Atkins’ Cutlass Supreme with two doors and a golden interior. In these cars, they went to each other’s places at night to work on new records and listen to the radio at the same time. Gary Numan in his 1979 hit sang: “Here in my car, I feel safest of all”. And Cybotron echoed him: “Sitting in my car, driving very far”. Cosmic cars is an escape from Motor City by any means: movement or inner emigration.

Afrika Bambaataa

Techno in the early eighties meant the definition of the sound, it was an epithet. Anyone can create something like this and even call it electrofunk. And in fact this happened. No one knew that techno of this time wasn’t the last metamorphosis of the style; techno as a genre branch was shaped only in the late 1980s and it was at the junction of electrostatic disco, synthpop and boogie. Afrika Bambaataa, who, together with Arthur Baker, a DJ from Boston, created an electrofunk which was similar to techno, was into the same things as Atkins. Bam: “This is [Kraftwerk] the music for the future and for space travels—along with the funk of what was happening with James Brown and Sly Stone and George Clinton. Of course, I was listening to a lot of Yellow Magic Orchestra and Gary Numan, as well as Dick Hyman’s Moog sound, and music from John Carpenter’s Halloween. When you put all that together, then you get electrofunk, which is what we were doing.” In 1981, the label owner Tommy Boy introduced Baker to Bambaataa who then was a musician and a DJ, leader of the Zulu Nation group, who took away talented boys from the hands of the street and taught them scratching, breakdance, graffiti and rapping—everything that would later become

Kraftwerk

Trans Europa Express / Numbers

According to one legend, Arthur Baker figured out what the next single should be while having lunch on the terrace or in the park. Trans-Europe Express, even four years later was all around buildings, constantly played in this area. At the same time, Baker went to a music shop for something new—his friends who worked there pointed to the Numbers single, for some reason released only in North America; the yellow 45’ with a throbbing rhythm sold in the Bronx like hotcakes. The musicians were severely limited in time and money: without a decent sampler or drum machine. Baker found an announcement in a newspaper:

Arthur Baker

Afrika Bambaataa & The Soul Sonic Force — Planet rock 1982

From Planet Rock single, Tommy Boy

Objectively, Bambaataa was in a better situation—the population of New York is seven times bigger than Detroit; the Bronx alone has nearly as many residents as Motor City. Unlike the jazz label Fantasy, to which Cybotron was signed, Tommy Boy didn’t have an extensive network of distributors, but he succeeded by including in the record additional breaks, a cappellas and long instrumental versions, that teenagers in parks and at parties played endlessly, training their bodies and rhymes. Before the Planet Rock single, Arthur Baker studied the musical preferences of young people with interest, who moved with Trans-Europe Express and the new album by Kraftwerk, Computer World—it just came out in May 1981: “Working in a record warehouse, I was really educated as to what people on the streets were buying, and whenever I heard Numbers being played at the ‘Music Factory’ in Brooklyn I saw black guys in their twenties and thirties asking, ‘What’s that beat?’ So I knew that if we used that beat and added an element of the street, it was going to work.”

Kraftwerk

The robots

1978

To be fair, by modern standards, the sound was too homegrown, but at the time, after rich and vibrant orchestrations flowing from disco, funk and soul records, fully synthetic music was seen as a transition into a different reality, where the recording of a hit could be done by one person without inviting masters. People who hadn’t heard electronic music before experienced a real cultural shock, as Atkins did while listening to the Dusseldorf hit The Robots open-mouthed. During this time, the shift in musical education, which used to be gradual, sped up. Conservatories didn’t teach how to use keyboards, they taught how to play the clarinet. What’s the point in notes if, after getting to grips with new equipment, you can play everything by ear? Innovators were inspired by Kraftwerk, who received classical training, but abandoned it, charmed by new technologies. Undoubtedly, even before Atkins and Bambaataa, the traditional American genres with almost unshakable foundations already drifted towards electronic sounds, but their presence was still partial.

They quickly found followers—young people dressed in something glittery and with faces covered with something cosmic. They released tracks, similar to the modern freestyle; Bambaataa said it was all the legacy of Planet Rock. The new robot music quickly became a part of mass culture. The postwar generation with the coming of the space age lived with the idea of a high-tech future and this topic was pushed up by the innovators in Detroit as well as in New York. Atkins was born in 1962 and Bambaataa—in 1958. This means that, since their childhood, they were brought up on Star Trek—the immortal

Ryuichi Sakamoto

In the new decade, all the equipment that was recently so expensive, became increasingly cheaper. The US of the 80s was led by Reagan and the energetic old man loosened the reins of business. In the US, where the cult of money exists, after financial losses throughout the 70s, extra money finally appeared and it was possible to live in grand style, buying art and Japanese equipment. Now every teenager passionate about music dreamed about it. After the devastating defeat in WW2 and the exit from voluntary isolation, the Japanese authorities and businesses, hand in hand, created a

A Number of Names

Sharivari

Ryuichi Sakamoto — Riot in Lagos 1980

From B-2 Unit album, Alfa

Herbie Hancock — Rockit 1983

From Rockit single, Columbia

Herbie Hancock

Electrofunk quickly gained national recognition—in 1983, the jazz musician Herbie Hancock in collaboration with a versatile producer Bill Laswell released the album with a very familiar name Future Shock, and the main hit Rockit with trendy scratching was played in a large installation with mannequins at the Grammy Awards a year later. (The jury didn’t know which category to assign the new trends to, and Rockit won a prize in the category of ‘Best Instrumental R&B Performance’. In 1998, dance (pop) music in the US—electronic music isn’t really in the mainstream—would get its own award Before that, mostly European musicians like Fatboy Slim, The Prodigy and The Chemical Brothers, who made a breakthrough in the US were included in the nomination for ‘Best Alternative Album’.) On the stage there were electronic drums, DJ turntables, animated androids in office suits breakdancing, and the forty-year-old Hancock with a portable keyboard over his shoulder, in white trousers, a silvery top and a half-zipped black leather jacket. Here it was, the future. At the end of the performance, the hall with six thousand people applauded him for a few minutes, including the future black King of Pop, Michael Jackson.

Atkins spent the summer of 1982, the year when Planet Rock came out, in New York. With two or three Cosmic Car boxes, he came to the capital of the world to promote his band’s sound. And he heard himself how the radio stations fought to the death to play Bambaataa’s single: “My concept was that the Kraftwerks, Telexes and Devos were good but they weren’t funky. I felt that if I could take that type of music and add a funky element to it then it would be a smash. We did that, but we just didn’t get recognised. Soul Sonic Force came along and beat us to it. The only thing was that Planet Rock was made in New York. They had the advantage of having the media behind them. Coming out of Detroit we were like number one on the local charts. It was all techno music basically.” Although, soon it all wouldn’t matter—Cybotron was disbanded in 1984 and electrofunk had lost its relevance by the second part of the 80s.

Music & stories

12″ pages on social networks and weekly materials that you can’t find on the website. Cool electronic music videos, tune of the week, histories behind albums and FridayFive tracks. Join!